Words by Curtis McGlinchey

Around 27% of children live in poverty in the UK. For many areas with existing deprivation the percentage is increasing every year. Frontline charities are left to deal with the consequences of overstretched services and the impact of the cost-of-living-crisis, one referral at a time. “We’re a little bit like Wombals,” says Ellie Brown, Charity Manager at Leeds Baby Bank. “We save a lot of items from landfill and take in things all the time; it’s a mixture of pre-loved and new – the baby bank is packed full of essentials that we think new mums and babies will need.”

It’s 09:30 and obviously a busy time for the team. There’s a muffled sound of productivity, of things and people moving about with places to go. Ellie apologises as she returns from helping a colleague. “We’re based in St Johns Centre in our own retail unit,” she says. “It’s perfect for the operation as we get racking and access to loading bays.” Ellie works part-time with four other staff members, including a driver (with electric van), and 25 volunteers – without which the charity wouldn’t be able to function.

They receive referrals for over 100 families a month from partners such as midwives and other healthcare professionals, with demand particularly high because of the cost-of-living crisis and increased energy bills over the winter months. The charity’s mission is simple: to help children living in poverty get the best start in life. Research published in 2022 from End Child Poverty and Loughborough University places Leeds East as having the 26th highest childhood poverty rate in the UK, mostly behind constituencies in London and Birmingham. Unprecedented demand means that they need to run as leanly as possible in terms of stock and staff.

So, what does a typical referral look like? There’s a shuffle of papers as Ellie looks for a referral note on her desk. “This one is for a mother who has had just had twins, so obviously we need two of most things,” she says. “Two cots, two slings, clothes, nappies, milk, two Moses baskets, a changing bag, toiletries. Sometimes mums forget about themselves, so basics like deodorant are important. I’m proud that we’re still able to offer our drop-in service at a children’s centre, where we give out essentials of all kinds – demand for this has gone through the roof.” This mirrors a national demand for daily basics at a time when choosing between heating and eating is becoming a normality for many families. A report by the Trussell Trust points out that compared to this time five years ago, the need for food banks in their network increased by 81%.

“It’s satisfying work because we know we’re making a tangible difference to the lives of mums and children.”

In an area that has higher than average childhood poverty, the community, with the help of local councils, are doing all they can to work together. “We share things with foodbanks and

have a good relationship with the council, which helps. We’re certainly one of the largest baby banks outside of London.” The charity was established in 2017 by a mum who began to encourage sharing baby essentials in her community. Six years on and the charity has recently won three awards: The Child Friendly Leeds Award, a council initiative that measures overall contributions to making Leeds a child-friendly city; The Mumbler (a network of hyper-local parenting websites) Best Community Project as voted by the people of Leeds; and the Compassionate City Awards community project of the year.

“Generosity is never in short supply at the baby bank.”

Ellie is rightly proud of their achievements and the impact they’re having, but a pat on the back isn’t the same as paying the bills. It does however speak volumes for the professional administration of the charity, the passion of volunteers and a service delivery aspect which some private companies could learn from. “It’s difficult not to put in extras when you get a packing list; I’ll drop an extra baby toy in or something. We’ve just started doing Mother’s Day packages that we’ll give out to help mums feel like someone is thinking about them.”

Ellie describes how they use a lot of blue Ikea bags for the packing, but they still have to purchase them. There’s a cost of doing business, even for charities. And besides, that one extra toy could push a standard issue plastic bag past its limit. Generosity is never in short supply at the baby bank.

“It’s satisfying work because we know we’re making a tangible difference to the lives of mums and children, but we also know we’re not solving the cause, that’s beyond our control.” Beyond regional investment choices, other factors are influencing life chances. Despite high rates of childhood poverty in London, social mobility index scores are much higher than in other parts of the country. Yorkshire and the Humber, the North East, and the West Midlands are the only regions to have no social mobility hotspots at all, according to the government’s Social Mobility Index of 2016.

Leeds Baby Bank might not realise it, but every toy, nappy, and bottle of milk is helping to bring opportunity to Leeds, and, at the very least, make childhood poverty a tragic hardship that shouldn’t have to affect the rest of someone’s life. They can’t put cash in people’s pockets, but they are investing in a better tomorrow.

READ MORE

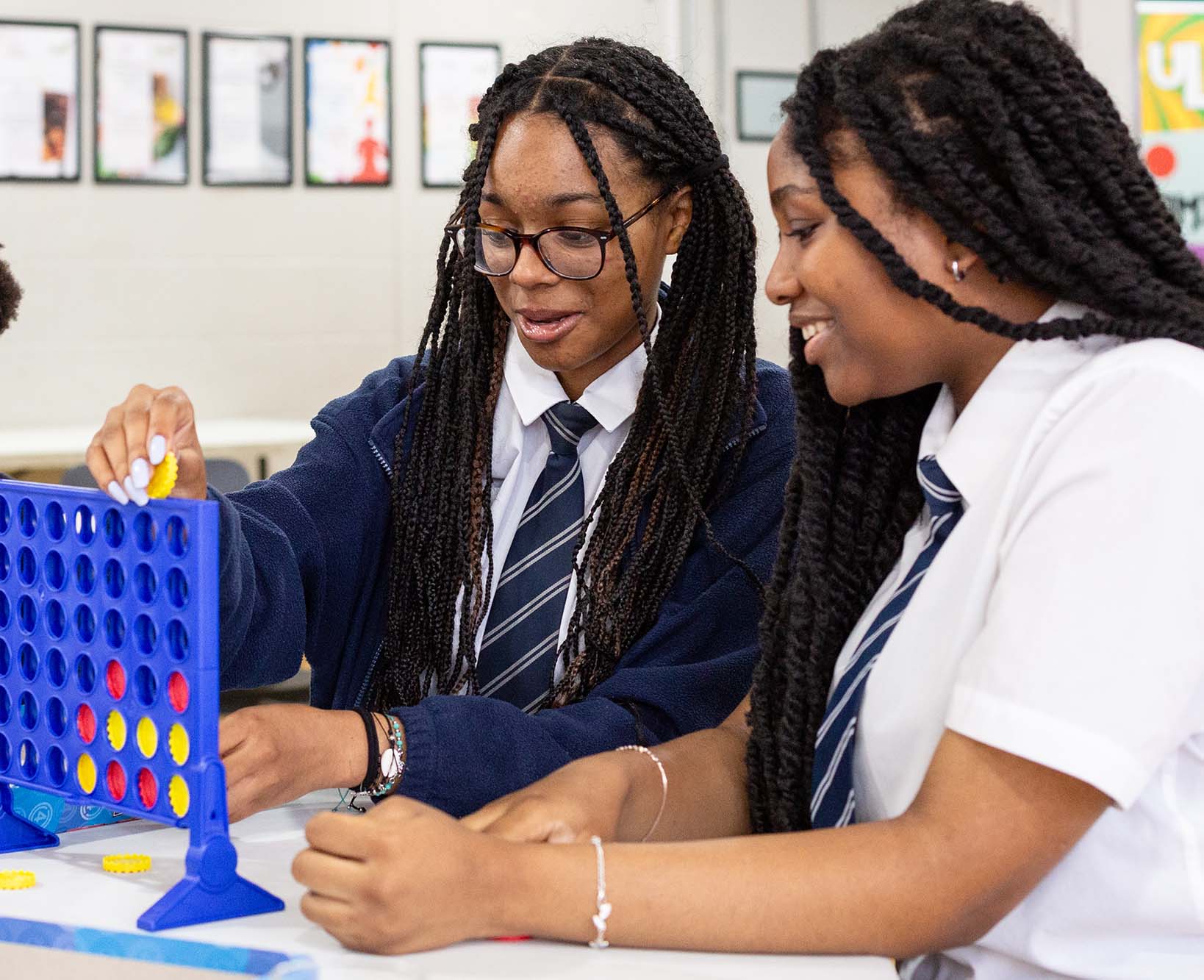

Unrestricted grant funding at the Leathersellers' Federation of Schools

At the Leathersellers’ Federation of Schools in Lewisham, unrestricted grant funding is helping pupils learn, thrive, and achieve their potential.

Hope and Vision

How the friendship between an offender and his sentencing judge offers a model for the rehabilitation of those struggling with addiction.

Visyon: Supporting Young People’s Mental Health in Cheshire East

The work of Visyon, a charity for young people, shows the power and potential of community-focused approaches.