“The Spreading of the Plague which is much feared”

London and the Leathersellers in 1665

Words by Jerome Farrell

In 1665 London was a compact but densely populated city of around 400,000 people – and a lot of rats.

Just as Covid-19 started in China, so the Bubonic Plague came, back in 1347, from the Far East. Within two or three years it swept through Europe with absolutely devastating effects, wiping out a third of the population. There were subsequent periodic and more localised outbreaks, which in London seemed to recur about every two or three decades. Particularly bad epidemics occurred in 1603 and 1625, but the worst – and as it turned out, the last was in 1665.

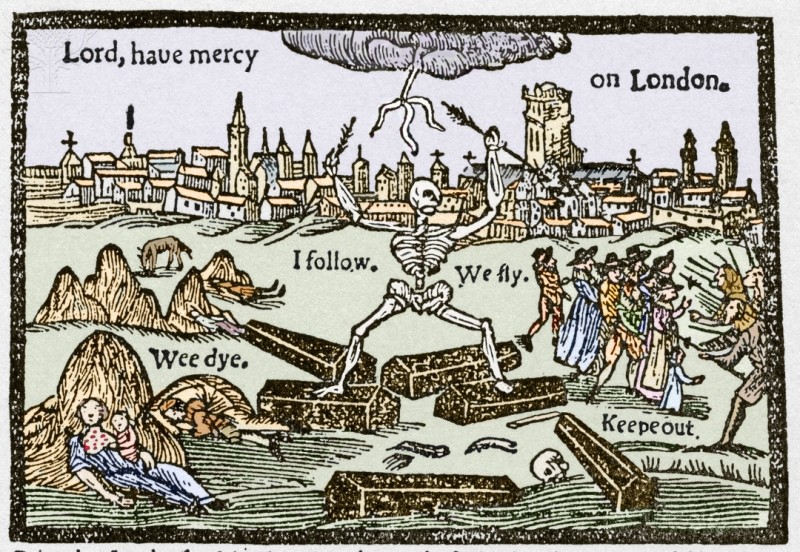

In the summer and autumn of that year, the plague escalated alarmingly. The Lord Mayor in 1665, Sir John Lawrence, a Haberdasher, together with the Aldermen (including several Leathersellers), issued Orders to contain the infection and avoid civil unrest. Lockdown and quarantine is nothing new. Infected persons were shut up with all their household, a watch kept outside and the door marked with a cross (which had to be at least one foot long) and the words “Lord Have Mercy Upon Us”. Food and provisions were supplied by the parish if people in quarantine could not afford their own, while dead bodies were removed at night to the local churchyard, or to special pits on the edge of the city. Infected beggars and homeless people were sent to ‘Pest houses’, where most of them died.

The Lord Mayor ensured that bread ovens were kept in operation, both to feed the people and reduce the risk of rioting. As was the case during Covid-19, gatherings at funerals were forbidden, though this proved difficult to enforce – Samuel Pepys refers in his diary to “the madness of the people of the town, who will (because they are forbid) come in crowds along with the dead corpses to see them buried”.

The City authorities issued an Order banning “disorderly tippling in taverns, alehouses, coffee houses, and cellars”, since these were the “greatest occasion of dispersing the plague”, and inns were only allowed to serve food and drink from their doorways, to be collected and consumed at home – in effect, takeaway only.

The Lord Mayor and most Aldermen remained in London, but King Charles II and his Court re-located to Hampton Court, and then Oxford, followed by Parliament. Those who could, fled to family or friends outside London. On 21st July, Pepys remarked on the number of “coaches and waggons all full of people going into the country”.

There was no real understanding of how the plague spread, but as today, it was surmised that gatherings of people were a cause of the infection multiplying. The Lord Mayor decreed that: “All plays, bear-baitings, games, singing of ballads, or suchlike assemblies of people, be utterly prohibited … and all public feasting, particularly by the Companies of this City, be forborne … and the money thereby spared, be employed for the benefit and relief of the poor, visited with the infection”.

We know now what our 17th century ancestors did not: that the plague was transmitted by fleas, living on rats, spreading the disease to humans. In 1665 they thought it spread through the air, or on clothing.

To dispel ‘bad air’, houses were fumigated and from the beginning of September 1665, fires were burned in the streets, for days on end. Sometimes this seemed to work – a mixture of brimstone, saltpetre and amber was burnt next to a house in Holborn where many had died, and no further plague deaths occurred there though this may have been because the stench and smoke acted as a deterrent to rats.

A form of personal protective equipment was devised in 17th century Germany and worn by some doctors in plaguestricken London. The protruding beak-like mask was made of leather and stuffed with sweet-smelling herbs in the belief that this would ward off infection. It was also thought that smoking or chewing tobacco, or keeping a gold coin in one’s mouth, would have a protective effect. Quacks and charlatans sold all sorts of items alleged to be effective against the plague, from “London treacle” (a compound of walnut, rue, salt and fig, to be swallowed each morning) to amulets containing toad poison.

The Plague and the Leathersellers

The Leathersellers still occupy the same site as in 1665, though were then in the second, rather than seventh, Hall. The Master at the time was Josiah Primate, a well-known merchant entrepreneur who promoted various extravagant money-making schemes, some involving coal and lead mining in the north of England. Primate knew Pepys (whose cousins William and Anthony Joyce, mentioned over sixty times in the diaries, were Liverymen of the Company) and tried to interest him in a £200,000 venture. Pepys was utterly sceptical and commented in his diary “God knows what it is”.

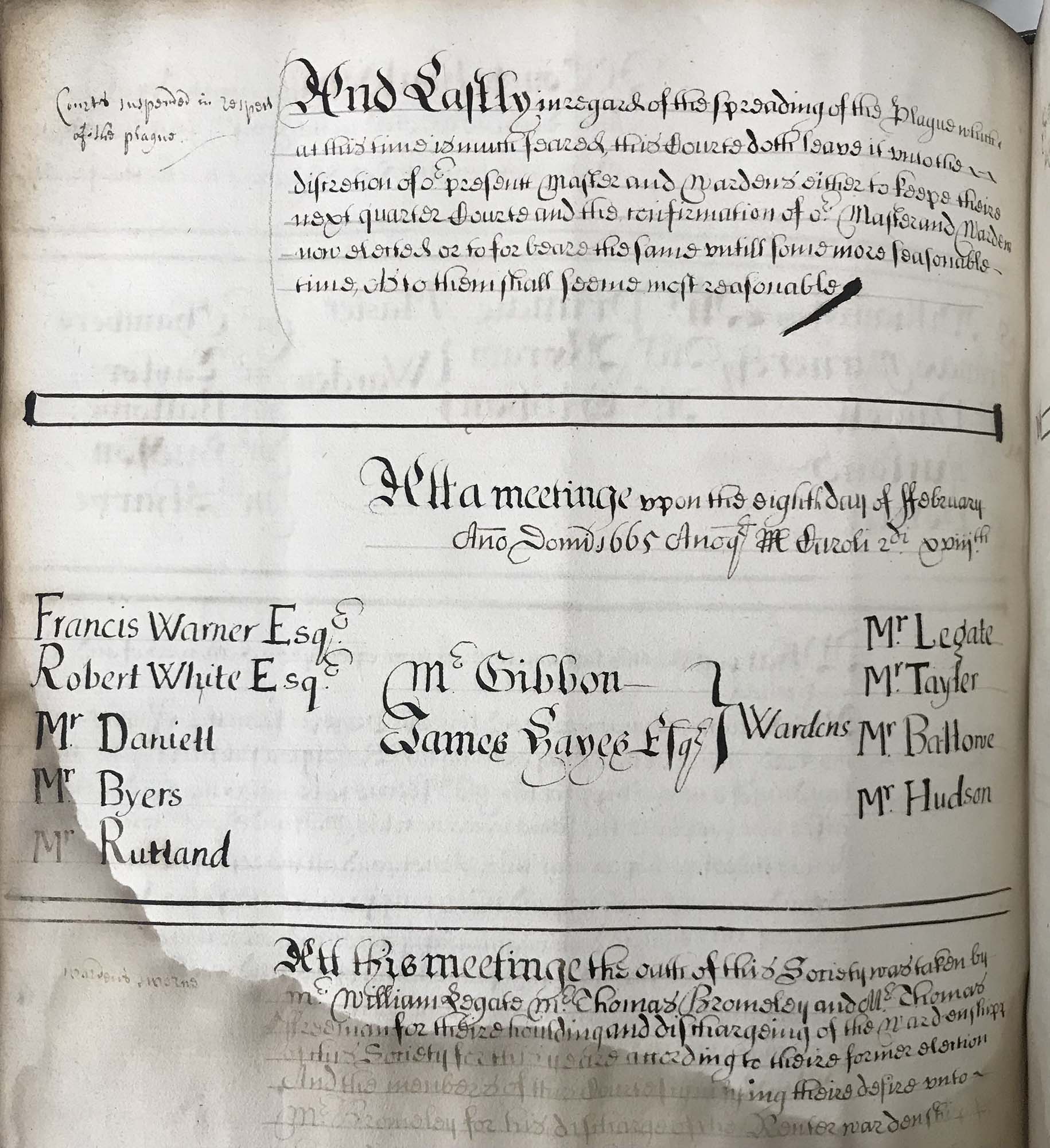

Fate decreed that it was Josiah Primate as Master Leatherseller who was confronted, towards the end of his year in office, with the dilemma of what to do at Leathersellers’ Hall as the plague rapidly took hold of London. Court Minutes, for the Election Court on 9th June 1665, say:

“And lastly, in regard of the spreading of the Plague which at this time is much feared, this Court doth leave it unto the discretion of our present Master and Wardens, either to keep their next Quarter Court and the Confirmation of our Master and Wardens now elected, or to forbear the same until some more seasonable time, as to them shall seem most reasonable”. The crucial decision which Primate and his Wardens then made is also recorded in the Minutes: Courts suspended in respect of the Plague.

There were no more Court Meetings or dinners that year and the decision was prudent and very probably life-saving – at least for the more senior members of the Company, some of whom are likely to have been among those Pepys saw “going into the country” in their coaches and waggons. The situation in London was getting worse and worse. Statistics were compiled and studied to try to discern the extent and pattern of infection. Weekly Bills of Mortality were printed, showing how many died, and the causes. By September, when the epidemic was at its peak, deaths from the plague numbered above 7,000 per week.

The Lord Mayor, Sir John Lawrence, lived in Great St Helen’s, just around the corner from our Hall. Before Mansion House was constructed a century later, the Lord Mayor often conducted business from his own home, and the Venetian Ambassador visited Lawrence in Great St Helen’s in 1665. The Ambassador described how Lawrence “being very fearful about the plague, has caused a cabinet to be made, entirely of glass, in which he gives audience, and determines the affairs of the City”. A slit allowed papers to be safely passed to him from the outside world. No illustration survives, but this may be the earliest reference to something with which we are all familiar today: a see-through screen to shield someone from infection.

Not surprisingly, as the crisis deepened, parish registers listing burials were often poorly kept and many deaths went unrecorded. Unfortunately this was the case at the parish church of St Helen’s, but the registers for the adjacent parish of St Andrew Undershaft – the church near the Gherkin – show the truly dreadful impact of the plague in this vicinity. Whereas in normal times about four people a month were buried in this small parish, by September 1665 that figure had risen to around four burials every day.

One plague death in these registers is of special interest to us: Thomas Tym, housekeeper, was buried the 9th of October 1665 of the plague. Thomas Tym was the Company’s Butler. At Leathersellers’ Hall it was not only the Butler who became a victim of the plague. Company accounts mention money spent on “newwhitting (whitewashing or painting) the Beadle’s house after they all died of the Sickness”.

At that time the Company employed two Beadles, and Leonard Pigeon, the under Beadle, died early on in the epidemic. His widow, Joyce, who followed him in turn to the grave in July, made a nuncupative will– a verbal expression of her wishes, in front of witnesses. Such wills were made when it was impossible to draw up and sign a document. The witnesses were two illiterate women – probably tending Joyce as she was dying.

In October the plague began to abate, though there was another spike in cases in November after the return of many who had previously fled the city. Then in winter it subsided further. By February 1666, after eight months, the Leathersellers resumed meetings at the Hall. James Hayes, who had been elected in 1665, was finally installed as the new Master, and crowned with one of the same Garlands still in use today. Attendance was poor at that first meeting but by the next Court Meeting, on 6th March, most of the Assistants were back at the Hall.

Comparing the 24 names of Court Assistants, before and after the Plague, only one, Benjamin Goodwin, does not reappear. That so many survived a disease which carried off about 20% – 25% of Londoners– around 100,000 people –suggests that most had fled the city. As with Covid-19, the plague hit the poorer classes worst.

Of the Company’s seventeen tenants living in our St Helen’s properties, right by the Hall, five appear to have died –a proportion much more in accord with the level of deaths in London as a whole.

Also very close to the Hall were our Company almshouses. These housed seven poor, elderly people – four men and three women (‘elderly’ was then defined as over 50). They did not fare well. Our 1665-66 accounts show expenditure on burying “some that died of the sickness in the Almshouses”. ‘Some’ is a vague term but suggests that at least three of the seven were plague victims. Because of the gaps in the registers at St Helen’s Church, we only know the name of one of these unfortunates, Edmund Milton.

London was devastated by this horrible disease. Eyewitness accounts describe corpses piled in heaps, and deranged and dying people desperately roaming the streets. Craftsmen lost their incomes, servants were abandoned, and thousands were destitute. The diarist, John Evelyn, coming into the City by coach on 11th October, was besieged by “multitudes of poor pestiferous creatures begging – the shops being universally shut up – a dreadful prospect”.

Most Livery Halls closed in June or July 1665, re-opening in January, February or March 1666. But not the Pewterers’ Company, who held Court Meetings at the height of the infection –and paid a heavy price. Their Upper Warden’s house was “visited by the plague”; their Master, Mr Seeling, who attended the 12th October Court, died four days later; and his successor, Ralph Marsh, elected on the 19th, died 24 hours later. The folly of meeting together in close quarters in an environment where the plague was already rampant is also reflected in the subsequent deaths of between eight and ten of their Assistants.

A systematic analysis of the effects of the 1665 plague on London’s Livery Companies has never been carried out. To date we have only partial evidence from some Companies, and know nothing about others. Walter George Bell’s book The Great Plague in London in 1665, published in 1924, remains a good in-depth account and mentions that both the Prime Warden of the Goldsmiths’ Company (Charles Everard) and a Past Master of the Brewers’ Company (John Bide, Master in 1643) died of the Plague, as did the Clerk to the Vintners’ Company. Nevertheless his book underlines that it was the lower echelons of London society which consistently suffered the most – those unable to leave the city and forced to remain in crowded and unhealthy living conditions throughout the epidemic.

What we know of the Leathersellers seems to confirm this picture. Josiah Primate may have been a wheeler-dealer, but he acted wisely in shutting down Leathersellers’ Hall promptly, and keeping it closed for eight months. By so doing he may well have saved some members of the Court from being carried off by the plague; most of them probably took refuge outside the city during the worst of the epidemic. The Clerk, Robert Harbin, certainly survived and he too may have left London – we simply do not know. But the Under Beadle and his family (the curt phrase “after they all died” suggests his household comprised more than just his wife Joyce), and Thomas Tym the Butler, died from the plague, as did a number of our almspeople and tenants living cheek-by-jowl in the congested lanes and alleys which then surrounded our Hall.

By 1666, the plague was over. But in early September, fire broke out in Pudding Lane and in just three days 80% of the City was destroyed, including 52 Livery Halls. Leathersellers’ Hall, fortunately, was in the one corner which escaped. But although loss of life was minimal, for those who lived through it the experience must have been traumatic. The Fire may be one reason why no further major plague outbreak occurred in London, as unknown numbers of rats and fleas were exterminated. Post-Fire London, built in brick rather than wood, was cleaner and less crowded. Also, in the years around 1700, the flea-carrying black rat was gradually displaced by the larger brown or sewer rat. These rats are still with us – but unpleasant as they are, at least we can be assured they are not spreading the plague.

READ MORE

Visyon: Supporting Young People’s Mental Health in Cheshire East

The work of Visyon, a charity for young people, shows the power and potential of community-focused approaches.

Boosting Opportunity at the Leathersellers' Federation of Schools

School led and backed by research a new social mobility project has created the dream job for Learning Mentor, Cherisa Kya-Scott.

The Story of our Almshouses

The story of Leathersellers’ Close begins in 1543 and is tied up inextricably with the move into the second Leathersellers’ Hall, the former nunnery of St Helen’s.