Identifying and supporting children with a parent in prison

A national, statutory mechanism to identify and support children with a parent in prison is within touching distance. While awareness and momentum around this national issue builds, the urgency is undiminished. Felix Tasker of charity Children Heard and Seen sheds light on the impact, scale and trajectory of the challenge at hand.

Words by Felix Tasker

Illustrations by Wimbledon High School for Children Heard and Seen

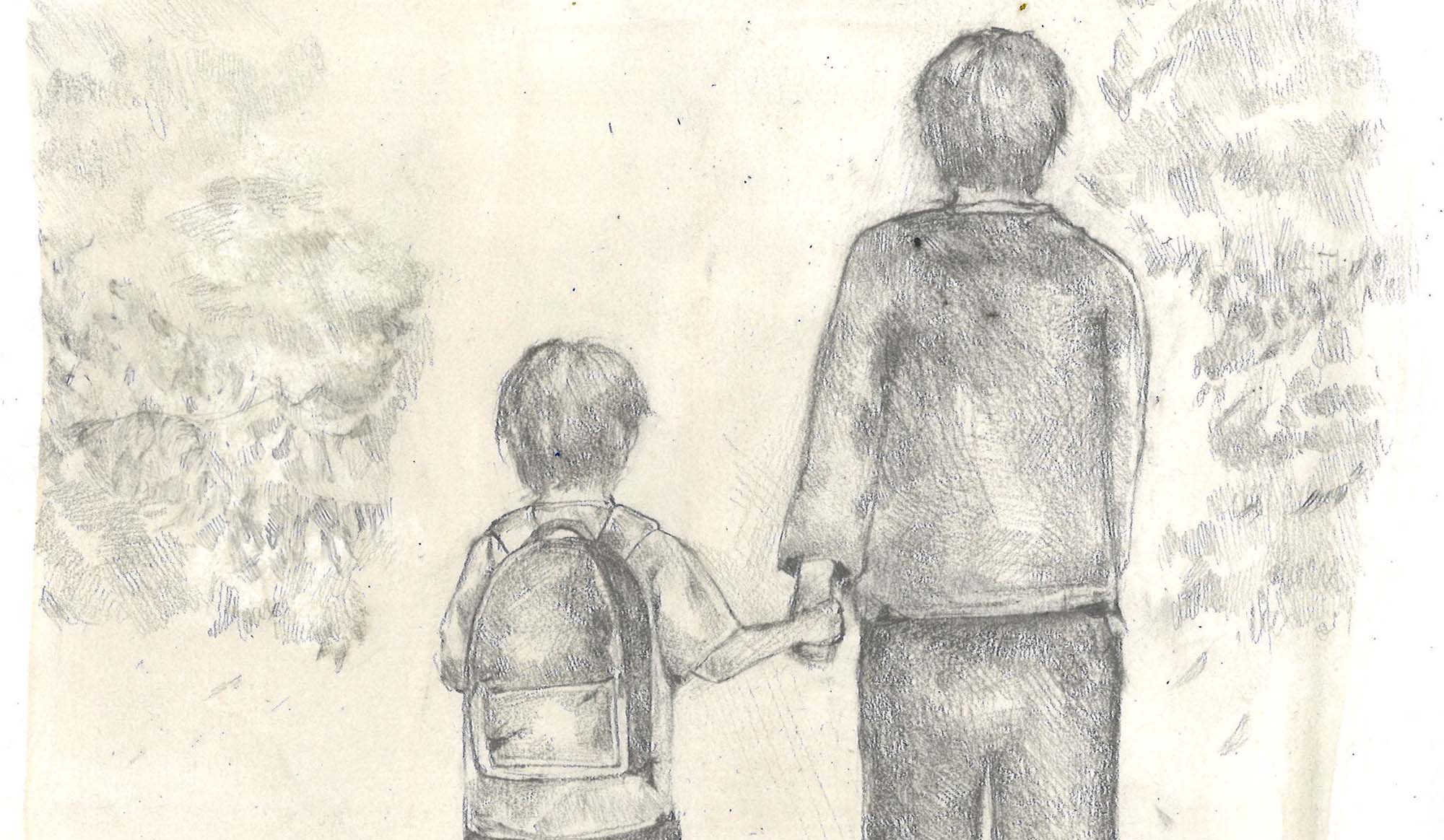

What happens when a parent goes to prison?

When Aaron* was eleven years old, his father was sentenced to a minimum term of 16 years for a violent, unprovoked murder. Overnight, Aaron’s world was turned upside down. His school noticed a sudden change in his behaviour, as he suffered from outbursts of anger in the classroom. Compounding his distress, Aaron became the target of bullying, as the details of his father’s crime and their home address were widely publicised. His mother, grappling with the issue of whether Aaron should have contact with his father or not, was left to fend for herself without any guidance or support.

Aaron is among over 190,000 children in England and Wales who are estimated to have a parent in prison. These children often become the ‘secondary victims’ of their parent’s offence, enduring consequences over which they have no control.

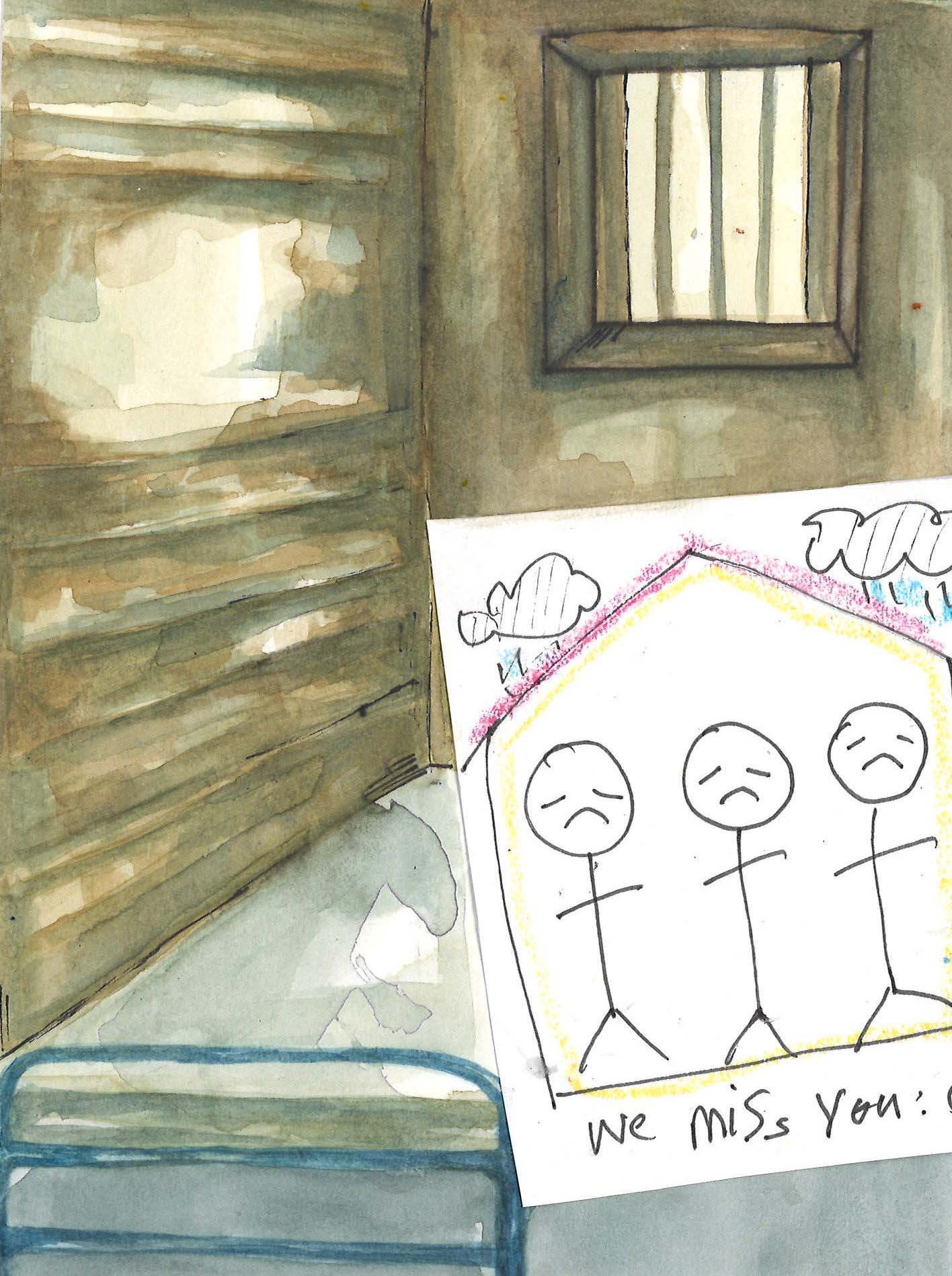

“They can feel isolated, ashamed and are more prone to mental health issues and poor educational outcomes than their peers,” explains Sharon Berry, CEO of Storybook Dads – a charity which helps parents in prison record bedtime stories and messages for their children. “It’s vital they receive support with regards to the specific needs associated with losing a parent sent to custody.”

Children with a parent in prison often experience a type of bereavement from losing a parent who suddenly leaves the home and never returns. However, in place of the sympathy and understanding that accompanies a bereavement, is often a prejudicial backlash from the community.

Andy West is a successful writer and published author whose book The Life Inside examines our prisons and the complex lives being lived inside. Andy’s father was in and out of prison throughout his childhood. “I had this obscure feeling of inherited guilt, inherited shame. This kind of ‘sins of the father’ anxiety,” he tells me, “like I couldn’t really claim any of my sadness or vulnerability I felt at the time, because I felt like I was implicated by association. It’s been a long time in recovering from that.”

In cases of more stigmatic crimes such as child sexual offences, children have been subject to vigilante attacks on their home, having to change their names and move hundreds of miles away. In the most extreme cases, children are left living completely on their own, without an adult to care for them after their parent is sent to prison.

It may seem unbelievable that this can be allowed to happen in the UK in 2025, but it is the shocking reality of a marginalised group that until now has slipped through the cracks in government services.

A's house was being targeted by vigilantes after a man had been sent to prison for sexual offences, and the vigilantes were not aware that he was in custody. After the family home was attacked, a Victim Support Caseworker attended the house and found the man's 15-year-old-daughter living at the address on her own.

A's house was being targeted by vigilantes after a man had been sent to prison for sexual offences, and the vigilantes were not aware that he was in custody. After the family home was attacked, a Victim Support Caseworker attended the house and found the man's 15-year-old-daughter living at the address on her own.

In the most extreme cases, children are left living completely on their own, without an adult to care for them after their parent is sent to prison.

Parental Imprisonment as an Adverse Childhood Experience

Having a parent in prison is officially recognised as one of the ten Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs). ACEs refer to potentially traumatic events in a child’s life that can affect their health and well-being. Research has shown that children who experience multiple ACEs, including parental imprisonment, are at significantly higher risk of poor physical and mental health, educational struggles, and behavioural issues.

This recognition of parental imprisonment as an ACE however has not led to any statutory responsibility to identify and support these children. Part of the issue is that currently parental imprisonment falls between the remit of the Department of Education and the Ministry of Justice. Without a clear idea even of the exact number of children in the country with a parent in prison, policy inertia has been exacerbated because of the unknown scale and impact of the problem.

Invisible Children: Falling Through the Cracks in Existing Services

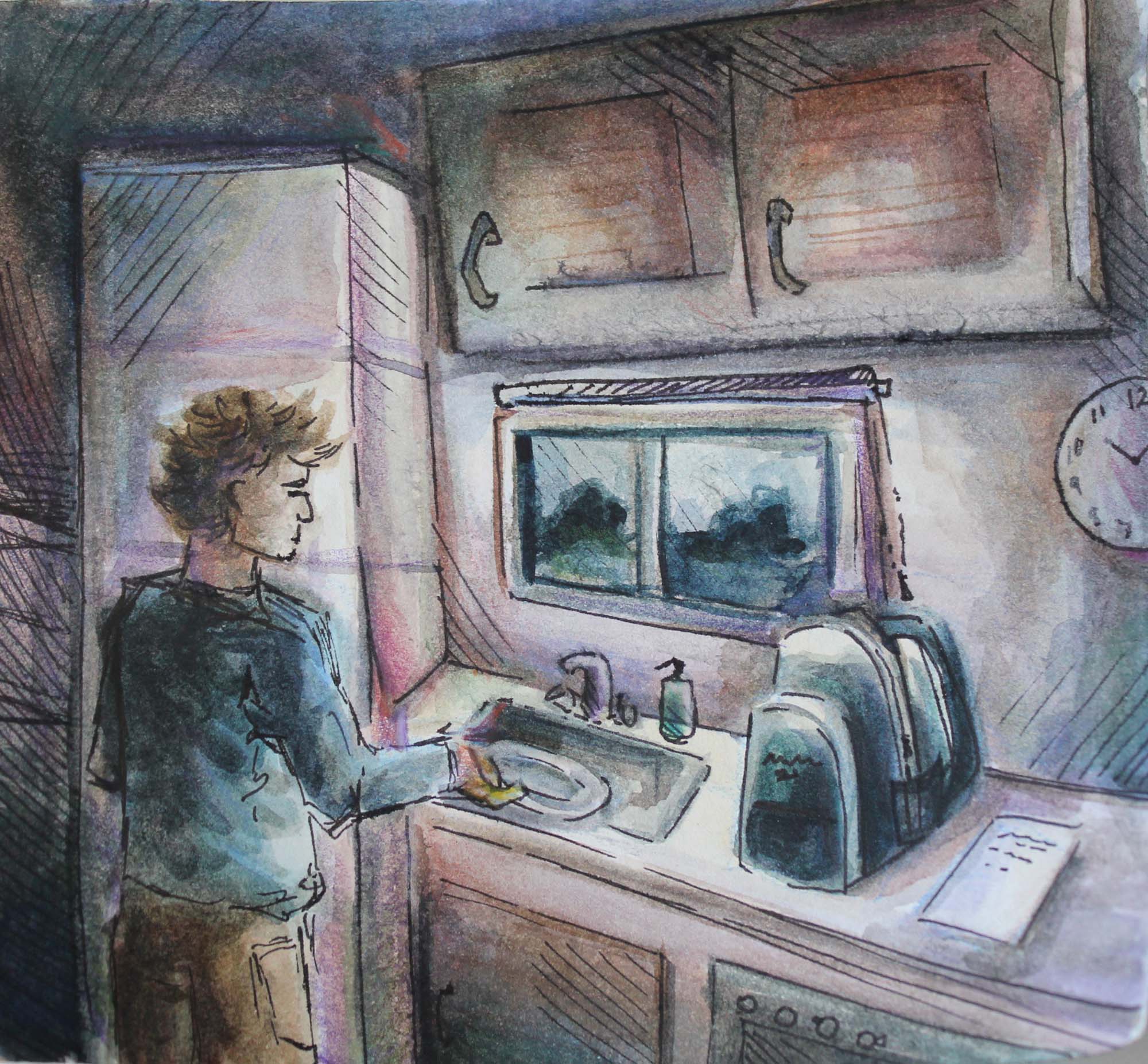

In theory every new prisoner is asked upon arrival if they are responsible for any children, however distrust and fear of authority often compels them to lie.

In 2022, the charity Children Heard and Seen discovered four instances in one month alone of children living completely on their own after their parent was sent to prison. In one case (pictured below), a 15-year-old boy was found living on his own, with no gas or electricity in the house, and had been going to school every day for months without anyone knowing his mum was in prison.

“I’ve come across families myself during the course of my work where a mother has come into prison and I’ve discovered that she’s had two children at home on her own – one 17, one 15,” says Dr Lucy Baldwin, Research Fellow at Durham University and a criminal justice consultant whose work focuses on the impact of maternal imprisonment, “and we had to find a way to get food and money to those children because they had nothing.”

The children in these examples were discovered by chance, highlighting a significant gap in systematic support. The stark reality is that no one knows how many more children there are up and down the country in this situation. Currently, children and families are left by the state to fend for themselves and find any external support they can. When they are able to access support however, the impact can be life changing.

Organisations such as Children Heard and Seen have shown that simple support, tailored to the individual needs and circumstances of the child in question can drastically improve mental health, wellbeing and change outcomes.

In Aaron’s case participating in group activities with peers facing similar challenges enabled him to recognise that he was not alone, reducing feelings of shame, stigma, and social isolation. Engaging in 1:1 sessions with a trained practitioner provided him with a safe, non-judgmental space to process the trauma and complex emotions surrounding his father’s imprisonment, leading to enhanced self-esteem and emotional resilience.

Aaron was also matched with a mentor who took him to exhibitions and supported his academic progress, all while providing a reliable and consistent male role model outside of the family home. Six years on from his father’s arrest, Aaron has received a 120% scholarship to a top independent school in the area, and is now thriving.

The scale of the issue of parental imprisonment however means that support cannot solely be provided through the charity sector.

“Families up and down the country are desperate for some kind of support, and in so many cases there is simply no provision out there,” explains Children Heard and Seen Founder and CEO Sarah Burrows, “Last week [February 2025] alone we had 77 children referred to our services. For a small charity it is unsustainable and the hundreds of children we are able to support are only the tip of the iceberg in terms of the overall picture.”

When the police attended this address, they discovered her 15year-old son living on his own. There was no gas or electricity in the house , and he had been getting up and going to school every day without anyone knowing.

When the police attended this address, they discovered her 15year-old son living on his own. There was no gas or electricity in the house , and he had been getting up and going to school every day without anyone knowing.

What is in the Child’s Best Interest?

Another challenge for organisations such as Children Heard and Seen, is ensuring that discourse and future policy around parental imprisonment always remains focused on what is in the child’s best interests, and support is not solely seen through the lens of the offender.

Government solutions often prioritise on facilitating visits and strengthening family ties between people in prison and their children, partly as this has been shown to reduce reoffending. However, what is not always considered is if that contact is in the best interest of the child in question, with respect to their own welfare and needs.

For some children with a parent in prison, emotions centre around missing their parent and wanting them back in the family home. For others however, they are glad they are now safe from their parent and are potentially fearful of their release. As Andy tells me, “When my dad went away, I felt relief because he was violent. It was good that I was protected from him.”

54% of children supported by Children Heard and Seen have been impacted by domestic abuse in the family home, illustrating the varied complex and difficult relationships children may have with their parent in prison.

The worry is that children are used as tools to reduce reoffending, rather their needs considered in their own right. Debra, whose father was convicted of murdering her mother when she was 13 years-old, recounts “When my father was first sentenced, social workers used to force my brothers and sister to go and see him in prison. They never succeeded with me, I just flatly refused to go.”

For children who do not visit their parent in prison, they are even further marginalised as prison-based family support services are not available to them. “These children are the hidden cohort within an already invisible group of children,” Sarah Burrows explains, “It is crucial that future policy takes into account the experiences of all children, regardless of their relationship with the parent in prison.”

As organisations working with people in prison vastly outnumber organisations working with children of prisoners, ensuring that the voice of the child is heard and represented in government policy remains a challenge. However, it is an issue that is gaining traction in Westminster.

While a criminologist was conducting research in a women's prison, one of the prisoners shared that her three daughters were living at home all on their own. She shared this information partly as she was worried they had no money for food.

While a criminologist was conducting research in a women's prison, one of the prisoners shared that her three daughters were living at home all on their own. She shared this information partly as she was worried they had no money for food.

The Current Political Context

In June last year, the publication of Labour’s election manifesto provoked interest and expectation amongst charities in the criminal justice sector. It included a commitment to identify and support children with a parent in prison, the first ever recognition of this group and commitment of this nature in any political party’s manifesto.

This commitment has been well received by many organisations, including Pact (Prison Advice & Care Trust), a national charity that supports prisoners, people with convictions, and their families.

“We welcome the Labour Government commitment to identify and support children with a parent in prison and the clear intention to involve families and the third sector in the policy making process,” CEO, Andy Keen-Downs says, “Children who lose a family member to imprisonment deserve to have their views heard and their feelings listened to, so they can be offered the right support at a time that is right for them.”

The raised profile and awareness of the issue of parental imprisonment has meant that a number of MPs have also stepped up to champion the cause of children with a parent in prison, ensuring their voices are heard, and holding the government to their manifesto commitment.

For example, Richard Holden MP (Conservative) and Jake Richards MP (Labour) appeared on BBC Radio 4’s Woman’s Hour in November 2024, as part of a weeklong series focusing on children whose parents are in prison, stressing the urgent need for a national system of identification and support for children with a parent in prison to become a reality.

It appears that knowledge about the damaging impacts of parental imprisonment on children is now widespread among key policymakers. The Department for Education has acknowledged that “growing up with a parent in prison can have a devastating impact on a child’s life chances”. Similarly, the Ministry of Justice has described children as being “locked in an invisible cell—one of separation, loss, and disruption.”

The key now, for individuals and organisations campaigning for change, is to ensure that the Government’s commitment to a system of identification and support for children with a parent in prison is not lost amongst competing policies and priorities.

A 16-year-old boy was arrested at the same time as his parents. When he was released shortly afterwards, he was left to be the sole carer of his 8-year-old brother.

A 16-year-old boy was arrested at the same time as his parents. When he was released shortly afterwards, he was left to be the sole carer of his 8-year-old brother.

What Would a National Statutory Mechanism Look Like?

Charities such as Children Heard and Seen believe that the establishment of such a system could be done swiftly, using existing data mechanisms. As Richard Holden MP explained in a recent Westminster Hall debate: “I say to the Government that there does not need to be a lengthy consultation. Children Heard and Seen has a ready-made solution. In collaboration with Thames Valley Police, it has created, in Operation Paramount, the first mechanism ever to identify and support children with a parent in prison.”

Paramount is currently live in Oxfordshire, Berkshire, Buckinghamshire and the West Midlands, and works by cross-referencing existing Prison Service and police data. Data which has previously only been used to track a prisoner’s movement through and eventual release from prison, is now being used to identify vulnerable family members left behind at the point of their imprisonment, and signpost to Children Heard and Seen’s services.

The Ministry of Justice is aware of Operation Paramount, stating that they “are continuing to learn from it to determine the best way forward to achieve our aims.”

Children Heard and Seen are advocating for the nationwide implementation of this system where, instead of the police, schools are promptly informed when a student’s parent goes to prison, enabling support within the educational environment. This approach mirrors the Operation Encompass model, which notifies schools of domestic abuse incidents. In this framework, third-sector organisations would continue to play a role by providing training to school staff and offering specialised support, particularly in cases involving serious offences.

Implementing a system where children receive immediate support after their parent’s imprisonment would significantly mitigate the negative impacts and help them reach their full potential. As Sarah Burrows puts it, “we just need the political willpower to make this happen.”

Get more information or support from Children Heard and Seen

READ MORE

The Educators

Meet the leatherworkers helping to give the UK its competitive and creative edge by passing on traditional leather craft skills.

The Embers of Shoemaking in East London

East London shoemakers are rekindling embers of the area's historic craft. Elisa Anniss meets the artisans making it happen.

The Rich History of the Leather Trunk

Rory FH Smith charts the evolution of luggage and the role of leather - a story synonymous with changes in transportation.