Breaking through the class ceiling

Lessons for social mobility

Words by Fiona Thompson

Photography by Jayne Lloyd

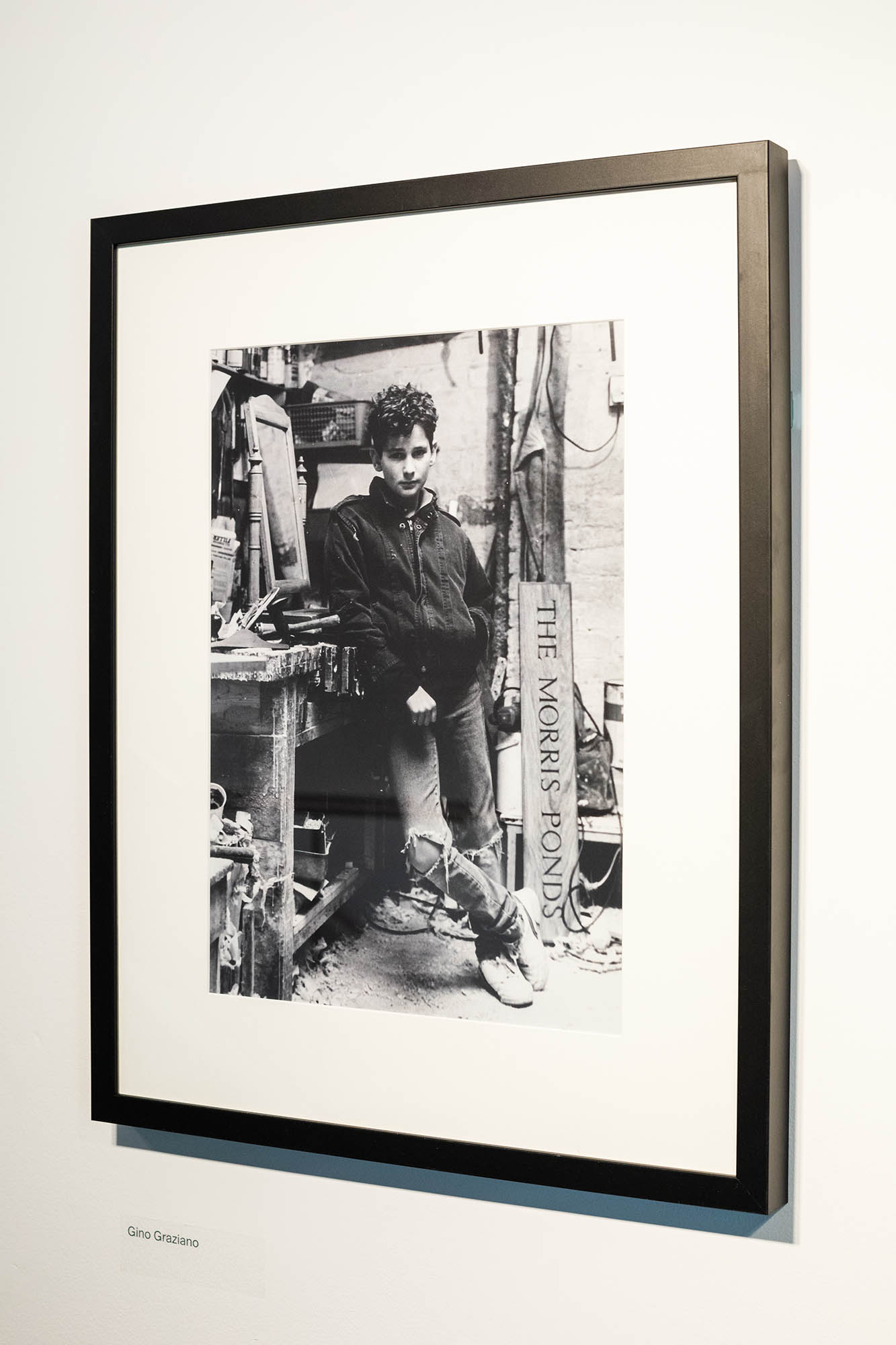

“This photo was taken in my dad’s carpentry workshop around 1990,” says Gino Graziano, as he looks at a black and white picture of himself aged 11 or 12. “I can still remember the smell of wax, wood dyes, glue, wood shavings and fag smoke. There was the background noise of lathes and the jigsaw, as well as the sound of argy bargy and banter, people buying and selling furniture and gossiping.”

The photo is hanging on the walls of The Class Ceiling, an exhibition at John Hansard Gallery, part of the University of Southampton. The show features photographs chosen by university students, staff and alumni who come from a working class background.

“For me, this isn’t a story of deprivation at all,” says Gino, who is now Director of Widening Participation and Social Mobility at the University of Southampton. “There are so many advantages to my upbringing. We were straightforward and upfront, with a sense of humour and respect. A lot of those assets are part of being working class and the privileges of having a really supportive family. I wouldn’t change it for the world.”

Having said that, he acknowledges that he did feel “a couple of pages behind in the book” during his degree in Cultural and Media Studies. “I didn’t really understand the terminology,” he says, “campuses, seminars, 2:1, that kind of thing. And in my early career working at universities I became aware of a difference in relation to middle class people who were much more at home in that environment.”

When we talk about inequality, we often think of age, disability, ethnicity and gender, but class is rarely considered. Yet when it comes to studying at university, a lower socio-economic class can create a range of barriers, from a lack of finance and an unwillingness to take on debt to a shortage of role models and less encouragement to take the leap into the unknown.

Research by the Institute for Fiscal Studies together with the Sutton Trust found that universities are important engines of social mobility, with the most selective institutions levelling the playing field the most amongst their graduates. However, most young people from disadvantaged backgrounds attend lower ranked universities, or don’t attend higher education at all.

“Class is the one of the unchallenged barriers in higher education,” says Heather Pasero, Career Consultant – Widening Participation at the University of Southampton.

“That’s why we originally came up with the idea for The Class Ceiling. We wanted to celebrate the working class – who we are, where we come from and what we have to contribute.

“We have an amazing new wave of employers in this country who are looking for graduates from diverse backgrounds. They value the unique attributes that working class students possess, including the resilience they have developed to deal with the challenges they’ve faced to get into higher education.”

When the call for photos for the exhibition went out, a few people at the university were concerned that they would be making themselves vulnerable by taking part. In the end, though, Heather says: “The response was phenomenal. A lot of working class people across the organisation breathed a sigh of relief. They feel empowered by seeing their stories reflected in the exhibition.”

Heather’s photo shows her as a baby in 1973 in her grandparents’ flat in Salford. The picture appeared in The Eccles Journal just before the family moved to a new life in Canada. “My dad was a steel worker,” says Heather. “Unfortunately, Canada didn’t work out due to social and health problems – what we’d now call multiple indices of deprivation.”

Later, Heather overcame numerous barriers to get into higher education. “My parents didn’t know how to support my studies while I was doing my GCSEs,” she says. “Meanwhile, my head was turned by boys and fashion and going out in the evenings. I did a Foundation course in Art and had to really fight for my place at university, which turned out to be life changing.”

At her Fine Art degree at Cardiff Metropolitan University, Heather says: “I met middle class people for the first time. They all seemed very at peace with themselves, less in survival mode.”

Savanna Cutts, Student Inclusion Manager, who has a photo in the exhibition, also had to overcome difficulties to make her way in the world. “I look at the picture of my younger self and I feel sad knowing the hurdles that lay ahead of me and just how hard I’d have to work and push. But another part of me feels proud of how strong I was then and how strong I continue to be.”

Savanna gained a first class degree in Law from the University of Southampton, but struggled with feelings of self-doubt. “Following my degree, I definitely felt imposter syndrome,” she says. “Class structures remain in evidence in higher education and I’ve had to acclimatise myself to an environment that traditionally doesn’t represent people from backgrounds like mine.

“I’ve used this as an opportunity to increase conversations around class in higher education, through founding the Social Mobility Network alongside my colleague, Gino Graziano. I’m proud of my working class background and the positive attributes I bring to the workplace because of it. It means I can take my lived experience and help under-represented students to succeed.”

In the exhibition, Liam Gifford, now Widening Participation Project Leader, is seen as a baby in his dad’s arms at a family event in a pub in Devon. Like Savanna, he also draws on his background to support working class students. “Southampton is a working class city,” he says, “so we should help people from lower socio-economic backgrounds to progress here.

“I’m proud of the university’s Widening Participation and Social Mobility work, as well as the tireless dedication of the Social Mobility Network.”

During his earlier teaching career, Liam gradually became aware of the barriers he faced and certain prejudices towards the working class. He says: “I didn’t identify my working / benefit / criminal class background as a barrier until I began to reflect on my role as a secondary school and sixth form teacher.

“That’s when I realised I was treated differently to my middle-class peers: promotion opportunities would go past me; my opinions would not be sought; my contributions (when heard) would be dismissed; I had to rely on humour to be seen; and senior staff would speak to me differently to me.”

Melissa Allada, an Equality, Diversion and Inclusion Officer at the university, has joined Liam to take another look at her photo in the exhibition. Her picture is of graffiti in Hackney Wick, the area of London where she grew up. It says ‘When I grow up, I want to be an apartment block’. She explains: “For me, the graffiti expresses the tension between locals who want growth for the community and the newcomers who can afford to live in the flats that are being built.”

When Melissa was growing up, the area was very diverse. She says: “It was a mish mash of cultures. Our neighbours were Nigerian, Ghanaian, Jamaican, Sri Lankan and Bengali. My parents, my sister and I crammed our lives into one bedroom in a house shared with five other Filipino families.”

Studying at university wasn’t an option. “I needed to find a way to get some money into the house,” she says. “I was interested in fashion so at the age of 17 I took an apprenticeship as a garment technologist with M&S. I was one of only two people of colour out of 200 people in my department.

“It was a completely different world for me. I didn’t know how to dress or speak to fit in with the corporate environment. Even the way I’m speaking now is different to the accent I have when I’m talking to my parents. I had to constantly switch between accents to fit in.”

After her apprenticeship, Melissa took on a role as a garment technologist, had a stint at the Department of Work & Pensions supporting vulnerable young customers, worked as Community Manager at an East London fashion hub, then joined the University of Southampton.

She now runs a variety of programmes, including a leadership programme that helps young people to progress. “It includes the norms of the corporate workplace that aren’t taught,” she says. “Things like how to dress, how to give a presentation, how to sign off an email. It helps build inclusivity in different ways.”

“Our neighbours were Nigerian, Ghanaian, Jamaican, Sri Lankan and Bengali. My parents, my sister and I crammed our lives into one bedroom in a house shared with five other Filipino families.”

Heather agrees that ‘codes of behaviour’ can be learned, but maintains that it’s important not to change who you are. She says: “I tried to change my voice for a while, but not for long. I think it’s a mistake to put on a silly posh voice, wear clothes you wouldn’t normally wear and try to be different from your family. Don’t pretend to be someone you’re not and run away from who you really are.”

The problem is that it’s not enough for someone from a lower socio-economic background to work hard and have talent. “Your background shouldn’t determine your success in life,” says Lee Elliott Major, Professor of Social Mobility at the University of Exeter.

“But too much is about where you live, what your parents do, the family’s income, and the opportunities and connections available through your family and your school. That’s what dictates your chances in life. The game is rigged so that the same people win. It’s a national scandal.”

Lee also has a picture in the exhibition, taken in the 1980s when his parents had split up and he’d been made homeless. After working as a road sweeper, friends encouraged him to go back to school and take his A levels. Subsequently, he won a place at Sheffield University to study physics.

Now his work focuses on working with schools and employers, challenging cultural norms to help make the world a more inclusive place.

So what needs to change to create a more level playing field in employment for people from working class backgrounds?

Gino believes that employers need to test their assumptions. He asks: “Why do applicants need to have a 2:1 from a particular university? Why do they have to present themselves in a specific way? Why do they have to talk in a certain accent? I know of people who’ve been told to take elocution lessons.

“That’s so daft. Why would you discount people who could potentially turbocharge your organisation just because of their accent? And why would you employ another candidate who’s less insightful just because they have a ‘better’ accent? We need to develop a healthy dose of understanding around the silliness and stupidity of classism and how it makes us a less competitive society.”

He believes it’s vital to challenge the barriers that are built into the system. “We have to understand the social class background of our workforces. We need to have benchmarks so we understand where the gaps are and how they intersect with ethnicities and gender representation. Then we can start to look at the nuances and complexities and create new approaches that support greater equality, diversity and inclusion.”

Melissa agrees, pointing out that: “True equity will only come from reducing the inequalities that exist before someone’s even born. That will take a massive overhaul of everything we know, from reducing poverty to investing more in health, education, social care and jobs.

“Organisations need to be aware that it’s not just about ticking off a checklist of diverse backgrounds and having one black person in a high-profile position. It’s about intersectionality. Recruitment must be non-biased and completely blind.”

As for encouraging more working class people into higher education, Heather adds: “We have to have better representation within the system, with more working class staff and academics being visible to potential students. The Class Ceiling exhibition has a role to play here, in sharing the academic and career journeys of working class people. It’s a window opening onto a changing world, where working class graduates are increasingly valued, sought after and celebrated.”

READ MORE

Behind the Wheel

Cars and leather have gone together since the birth of the automobile and, though the industry is pivoting towards electric vehicles, it remains convinced of the sustainability, luxury, and durability of genuine hide interiors.

The Educators

Meet the leatherworkers helping to give the UK its competitive and creative edge by passing on traditional leather craft skills.